Consultant Burnout

Michael D. Mitchell

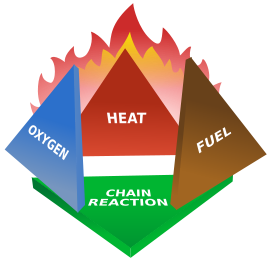

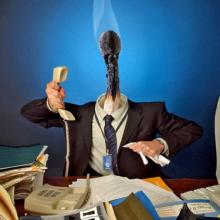

The term “burnout” is very graphic – suggestive of extinguished fires and charred remains – and one may well wonder how it relates to consulting and what consultant burnout means.

As I have come to know the burnout phenomenon – by living through it and from conversations with many consultants – it involves a “using-up” of energy and of the “internal fires” that drive an individual. To say that someone is “in burnout” then is to say that he or she is somewhere in a progressive process of fatigue and depletion of personal resources.

A consultant who has a project scheduled to begin the next day but feels somewhat depressed and unwilling to go; a consultant who glances at his watch when

working with a group, thinks about going home in twelve hours, and suddenly realizes that he has not heard a word said in the group for the last ten minutes; a consultant who begins to muse about his own career plans – doing what he “really wants to do” – and then becomes aware that none of the things that occur to him even remotely resemble conducting a project like the one in which he is involved – these are examples of consultant burnout.

Internal Drive

Many consultants are indeed driven by internal fires. Perhaps we see other possibilities, new alternatives for living in organizations, alternatives that we focus on because:

– despite our insistence on pragmatism

– we are often idealists. Many of us are in the field because the work

we do is consistent with our values: we get satisfaction out of helping others

and making the organization effective.

If this is admirable, it also makes us vulnerable to burnout.

Non Association

When I say that burnout is a depletion of the internal fires that drive a consultant, I mean that the energy is reduced; I do not mean to suggest that

the values behind the energy are necessarily modified. Of course, idealism is not the only factor that motivates consultants. The need for achievement, the desire for pleasure in one’s work, the inability to say no to clients, the hunger for work, the fear of failure, the fear of not being fully utilized, the need for acceptance and affiliation – these drives are familiar to many of us.

Boundaries

Although this paper is directed to the phenomenon as it affects consultants, burnout is certainly not limited to organization specialists. On the contrary it seems to afflict people in a wide range of helping professions. It seems to occur because of the often non-reciprocal balance of the relationship

between consultant and client. The relationship is often characterized by giving, supporting, listening, empathizing – much investment on the part of the consultant with little feedback or even acknowledgment on the part of the client. Although non-reciprocity is inevitable and acceptable, it is also draining. No one can function long in a helping profession without feeling its impact.

In fairness to clients, responsibility for the non-reciprocity is partly the consultant’s. Many professionals have a need to give and to overwhelm themselves in the consultation/helping process. I cannot count the consultants I have talked to who have no time for themselves, who live in hotels, whose marriages dissolve while they seek desperately to meet all the needs of all their clients. Being overwhelmed with work has many gratifications, but it has a tendency to be self-destructive.

Burnout Stages

When one is in the process of burnout, a series of progressive stages are involved, although each person may have different symptoms and varying rates of

progression. Burnout typically begins after several years of strenuous professional activity. In my case, it was after three years of on-the-road consulting. The more intensive one’s personal professional investment, the more rapidly one can expect the stages of burnout to appear: stage one, physical fatigue; stage two, psychological fatigue; stage three, spiritual fatigue.

Physical Fatigue

At his stage of burnout, the consultant often feels tired, dragged out, and lethargic. Some of the fatigue is real, caused by long ours, jet lag, and intensive, demanding work – but part of it is not. The consultant simply feels drained. Whereas a good night’s sleep used to take are of rejuvenation, now it no longer brings recovery. Colds, flu, aches and pains also seem to be ore common. If the consultant does not onsciously do so, his or her body may take responsibility for temporarily ithdrawing him or her from action.

Psychological Fatigue

This stage includes many of the physical symptoms, and more. It involves an alienation from clients and from tasks facing one and a significantly increased desire for variety and uniqueness in consulting activities. The consultant not only tires easily, but he finds it difficult to invest as much in the clients as before. Clients can seem grasping, self-centered, and unappreciative. The consultant may have the feeling that he or she has to conserve energy because “everyone wants a piece of me, and there is not enough to go around”.

Many of the symptoms of this stage may be quite unconscious, but they are recognizable: spontaneous feelings of depression when traveling to client

meetings, increased irritability and susceptibility to minor trauma, unconscious avoidance of present and potential clients, and increasing sensations of déjà vu in consulting situations. The consultant not only craves greater uniqueness and newness in his or her work, but at the same time experiences a reduced ability to see the uniqueness that actually exists in ongoing relationships. Feeling very much alone, alienated, tired, and bored, the consultant easily moves into the third stage.

Spiritual Fatigue

This stage is a natural consequence of the one preceding it. As the consultant progressively feels unable to invest in other, threatened by others’ needs, and drained of energy and interest, he or she turns, consciously or otherwise, to thoughts of escape. The consultant thinks about changing jobs, “hiding out” for a while, moving to a different area, or even moving into an entirely new profession.

Consultants at this stage frequently find themselves doubting their effectiveness (Do I really have an impact?), their values (Who am I doing all this for,

anyway? Is it worth it?), and perhaps even the morality of their efforts (Have I really helped the organization, or have I just set up the people to get hurt the next time there is a power shift?).

At this stage, the consultant’s ability to invest in clients drops even lower. This lack of involvement and the consultant’s own state of personal peril are communicated all too clearly to the client. The client’s ability to derive help from the consultant decreases proportionately. Client relationships weaken, and some drop away. The perceived time for change has materialized.

Coping

Consider for a moment the consultant’s dilemma. Like a priest or minister, the consultant sees a better world. He or she believes it can become reality yet

knows the inappropriateness of “selling” it. It has to be modeled, to be demonstrated, to be made easily available to others. Too, the work of the consultant

is often intangible. Not only is the impact of his or her efforts rarely visible directly, but there is a dynamic quality to individuals and organizations that tends to blur the importance of the consultant’s contributions to perceived changes. There is also the sensation of impermanence. Time moves on (What have

you done for me recently?). Additionally, the needs of the client cause them to take more and more from the consultant. The consultant feels less and less able to be human and more and more like a dispenser. And on top of it all, there is the continual aloneness – often simply a result of the way the consultant works – that leaves the individual little time to devote to his or her own needs.

How does one cope with this dilemma? I think the answer is obvious: take care of yourself.

- Put limits on your consulting time – both in terms of hours per day and days per month. Treat your limits with respect.

- Set time aside for yourself and use it, even if you feel “high” and think you do not need it. If you do not need it now, you soon will. Reserved personal time (one week out of five, two days per week, and so on) serves replenishment needs for the consultant in the same way that sabbaticals do for teachers and retreats do for religious leaders. Do not be ashamed to recognize and meet your own needs.

- Work with co-consultants – particularly with people you like – whenever possible. It is not only fun and potentially more productive for the client, but when you team up with a colleague, you are reducing the chances of your own depletion. You may even achieve some replenishment.

- Develop long-term consulting relationships. Maintaining ongoing relationships with clients allows the consultant to avoid some of the alienation and aloneness of the “hired gun” professional. Not only is the work likely to be more enjoyable, but the chances are greater for the consultant to see the results of his or her efforts.

- Arrange to be with “significant others” on a regular basis, if possible. You need support, recognition, reassurance, and opportunities to step out of your consulting role in order to share your feelings and thoughts with others.

Whether as a prevention of burnout or as a response to its symptoms, I think the foregoing are the requisite coping mechanisms. Of course, there are other possibilities, including the following:

- Limit your investment in clients. This is a theoretical solution only; personally, I do not know how to do this. For instance, if I am working with a client, I begin to care about that client, and as I care, I invest. If you can limit your investment, however, I recommend trying it.

- Limit your clients. This is more practical, but not many consultants seem willing to do it.

- Change your career. This is drastic, but there are many who have responded to burnout by doing exactly that.

Concluding Thoughts

Consultant burnout may not be inevitable; neither may it be avoidable. It is, instead, common, tremendously debilitating, and likely to be unrecognized for what it is until the symptoms become problems. For the internal consultant, the difficulty of coping may be greater than for the external consultant, who has greater control of his or her time and can thus schedule “personal time” without confronting organizational constraints.

It is clear that the consultant can gain a great deal from the experience of burnout:

(1) a realization of his or her own limits and fragility;

(2) an acquisition of the skills for renewal, as the consultant is forced to pay attention to his or her own needs;

(3) a strengthened commitment to changing ineffective behaviours and nonproductive investments;

(4) increased personal growth as a result of struggling to cope with and to reduce the pain of burnout.

One result that burnout does not produce, unfortunately, is immunization from burnout in the future. It can occur repeatedly, or it can stretch out, with minor regressions, over a period of years. Both for consultants who have not experienced burnout and for those who have, coping with its causes will

continue to be a necessity.

Need Help in Getting Your People on the Same Page?

Ask Nick Anderson

Focusing Change To Win’s Co-Author

[contact-form subject=”Feedback from pdsgroup.wordpress.com” to=”nanderson@thecrispianadvantage.com”] [contact-field label=”Name” type=”name” required=”true” /] [contact-field label=”Email” type=”email” required=”true” /] [contact-field label=”Industry” type=”text” /] [contact-field label=”Feedback” type=”textarea” required=”true” /] [/contact-form]

___________________________________________________

© Copyright All Rights Reserved, The Crispian Advantage. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Nick Anderson, The Crispian Advantage and Walk the Talk – A Blog for Agile Minds with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.