Developing Better Job Information

Developing Better Job Information

Introduction

This paper is based on John Machin’s early research in the 1970’s when his team developed the concept of aligning expectations into a useful communications improvement process. It has been validated by our development of sophisticated, easy to use Technology – AlEx™

Both Machin’s work and our AlEx™ projects show that most organizations have found that the AlEx™ expectations data-base demonstrates that:

- Individuals with identical job descriptions actually carry out their jobs in different ways

- Detailed information about each job in the expectations database is significantly greater than that in most job descriptions

- Detailed information about each job in the expectations data-base is more up-to-date than most, if not all, job descriptions

- Easy access to the data-base, using AlEx™ enables people to keep job information up-to-date much more quickly, easily, and usefully than is the case with traditional job descriptions.

Different job’s interpretation and implementation raises a number of questions, ranging from;

‘Why have job descriptions anyway?’ to ‘If there’s actually more individual freedom to “tailor” jobs than job descriptions appear to indicate. How can we use AlEx™ to extend that freedom in a planned and controllable manner?’

When individuals have identical job descriptions, there is an expectation that each person will performed in the same way. In jobs where all the tasks are programmable this is realistic. Fortunately, technology created an era where many people are no longer expected to perform such jobs. Now, invariably, it’s the user who determines which purpose will be followed within their team. The following case study illustrates that range.

The Royal Navy – A Case of Three Frigates

(Abridged and excerpted from the original John Machin case study)

The Royal Navy has many units which are ostensibly identical. Like a squadron with several frigates performing identical tasks, each of them with exactly the same chain of command and complement on board. The frigates were all constructed to the same design, and their captains were accountable to the same shore-based commanding officer. Other constants were:

- All individuals employed within the Navy at a particular level share the same training and basic experiences

- Each job on board a frigate has a series of officially drawn-up statements about:

- The role to be performed

- The responsibilities expected

- The authority and accountability that would be used to monitor progress

The Royal Navy anticipated that exactly the same communication content and pattern would be found on board the three frigates. The Navy was aware that it is always possible to improve, and it therefore undertook a communication audit, using the Expectations Approach (AlEx™), on board three frigates in the same squadron.

The Communication Audit Results

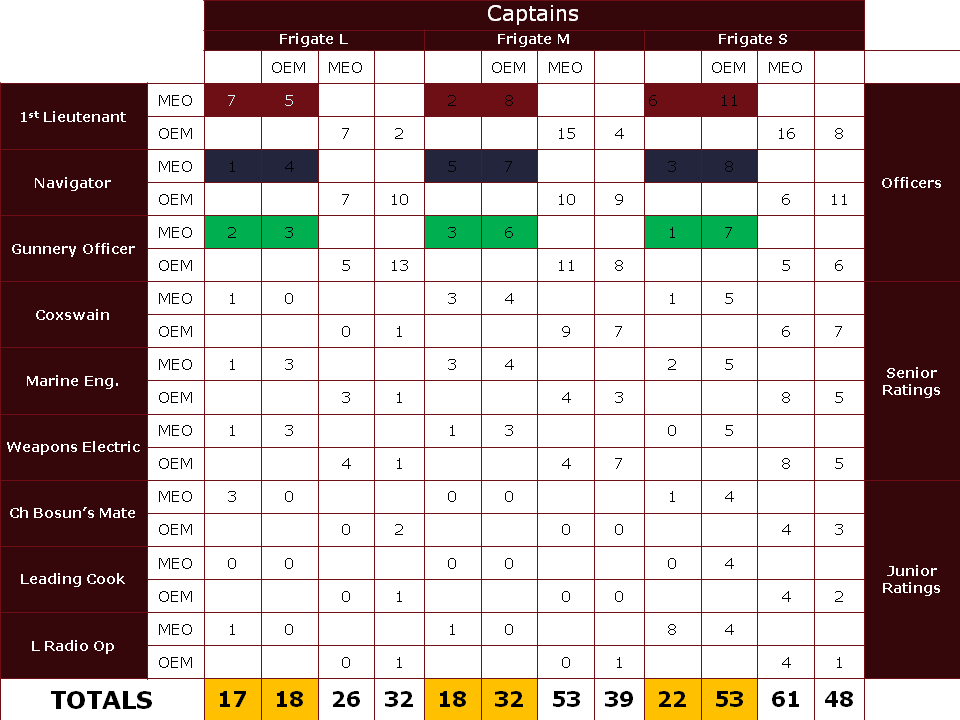

On each frigate, 10 crew members were chosen to take part in a single stage communication audit. These 10 held exactly the same positions.

Each person received a communication audit report. The Matrix summary of the results follows showings the expectations volumes by the Frigates L, M, and S captains.

In the center two columns under each ship’s letter are the Captains’ Expectations:

OEM – What I think others expect of me

MEO – My expectations of others

The outside two columns show the expectations of the Captain by the other nine participants listed on the left hand side.

Royal Navy Comparative Ship-Board Expectations Matrix

Royal Navy Comparative Ship-Board Expectations Matrix

While the communication audit was being carried out on board the three Frigates, shore-based personnel were also auditing their own communication. The general view, both ashore and on the frigates, was that while there might be considerable mismatch of communication on shore, the communication content and patterns on board ship would be common in all three ships. Clearly this not the case!

The first indication of this lack of commonality is the different volumes of expectations: Frigate L – 93, Frigate M – 142, Frigate S – 184

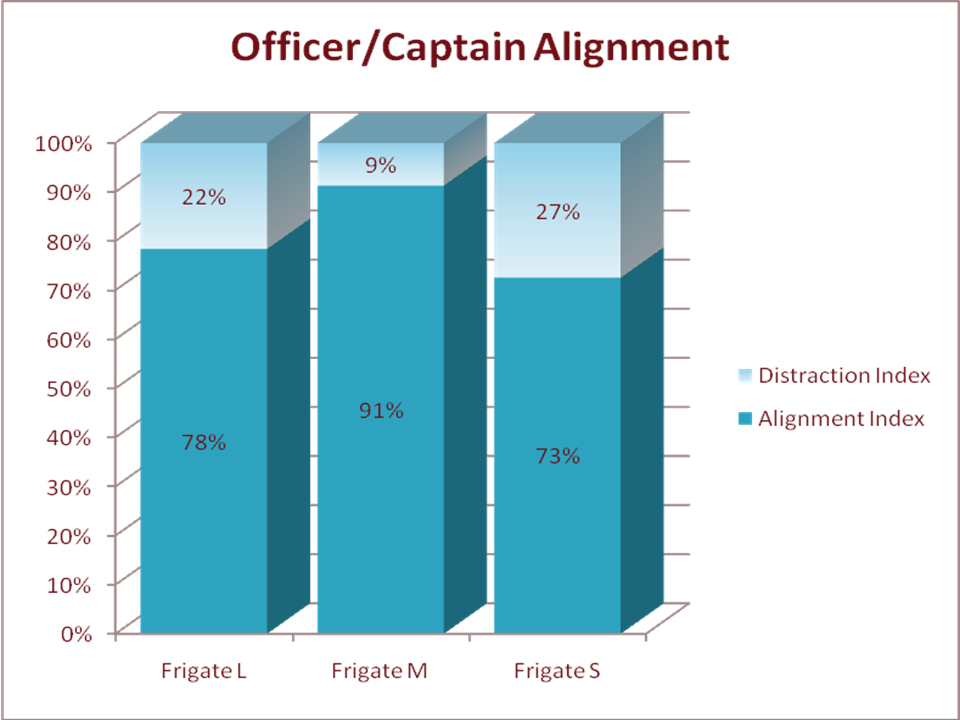

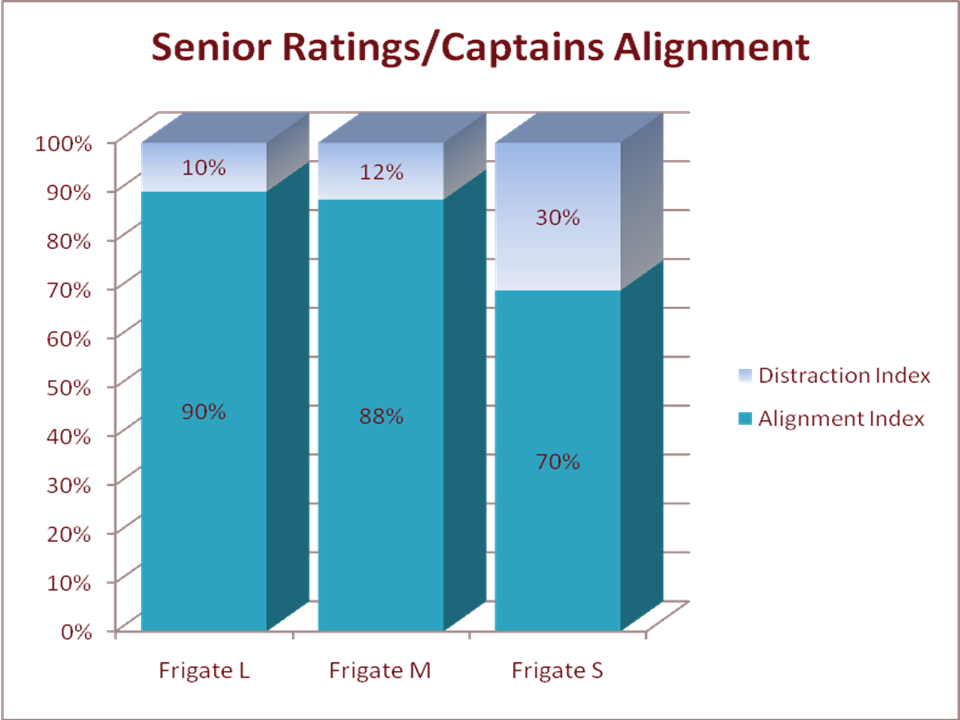

Next, looking at the different distraction indices between Captains and Officers then Captains and Senior Ratings (Distraction Index – the extent to which expectations are not matched or reciprocated.)

The Second indication was that the Captains and their Officers had markedly different distraction indices. Third, see the 30% diference in Frigate S.

Junior Officers

The Captains of frigates L and M expressed no expectations of any kind in respect of their junior officers. They neither held actual expectations of them, nor did they think the junior officers to expect anything of them. With minor exceptions that was the view that the junior officers themselves held in respect of the Captain. On frigate L the Chief Bosun’s Mate and the Leading Radio Operator both expected two-way communication of expectations with the Captain but in frigate M only the Leading Radio Operator expected any form of communication with their captain.

The Captain of frigate S held a number of actual and perceived expectations of all his junior officers. This was reciprocated by the junior ratings, with only one exception.

Conclusions

The communication Audit endorsed why Frigate M was rated best based in Operational Performance Reviews. Overall, M had a 0% distraction index rating while L and S were 14% and 18% respectively. Subsequently, another audit showed Frigate M was best aligned with Shore Based People and deepened the understanding of how alignment played a material role in a ships operational readiness.

The Senior Officer felt the analysis showed two main conclusions:

Each participant in each frigate was presented with his own report and the reports of his two opposite numbers in the other two ships. He was then asked to select the most accurate and appropriate expectations for his job from all three reports with a view to achieving a common outcome.

It rapidly became apparent that while the three job holders of the ten jobs could reach agreement, on some the communication associated with the job, agreement still ranged from 7.5%-88% .

Our conclusion is that even in tightly controlled environments like these three frigates can show such misalignment, what does this imply for other organizations? It clearly demonstrates that relational alignment of expectations is needed for effective performance to flourish.

Great, but how can this help me?

This is probably the first thing on your mind after reading this Blog.

How about asking us? The first call is free! Just email me to set it up.

Don’t wait, get The Crispian Advantage working for you!. If our conversation leaves you needing more, we offer at a reasonable fee telephone and video coaching improve bottom line results.

If that still doesn’t do it, we’ll work with you on a solution.

[contact-form subject=”Feedback from pdsgroup.wordpress.com” to=”nanderson@thecrispianadvantage.com”] [contact-field label=”Name” type=”name” required=”true” /] [contact-field label=”Email” type=”email” required=”true” /] [contact-field label=”Industry” type=”text” /] [contact-field label=”Feedback” type=”textarea” required=”true” /] [/contact-form]

_________________________________________________________________________

For Help in Getting Your People on the Same Page

Nick Anderson, The Crispian Advantage

© Copyright All Rights Reserved, The Crispian Advantage and Walk the Talk – A Blog for Agile Minds, [2010-2012]. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Nick Anderson, The Crispian Advantage and Walk the Talk – A Blog for Agile Minds with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.